‘Who is Not in the Room’:

Exhibiting and Experiencing the Disabled body in Museum Fashion Exhibition

‘Who is in the room? Who could be in the room? Who should be in the room? And how do we bring them in?’

(Sinéad Burke, 2019)

(Sinéad Burke, 2019)

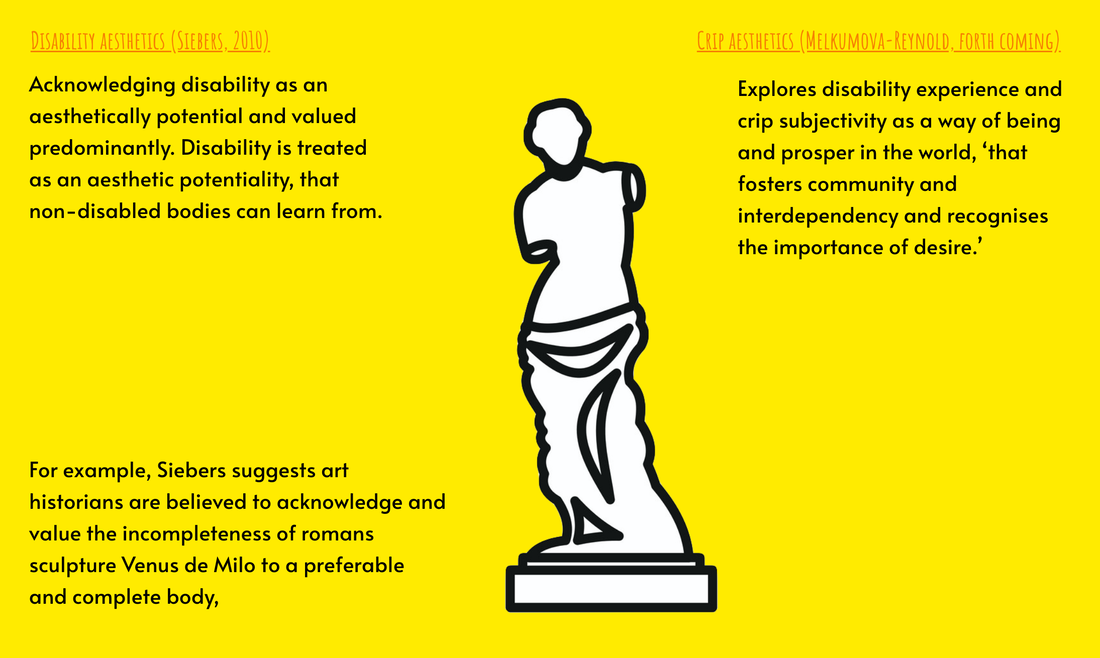

This study discusses how museums curate and represent disabled bodies, and how disabled people experience in museum exhibitions, to discuss appropriate narratives and representation of disabled people in fashion exhibition. Fashion exhibition is a powerful media in social and cultural discourses production, unlimited to fashion; whereas experience of disabled bodies, how one senses and being in the world, is a valuable field yet to be explore. This analysis aims to contribute to the concept of ‘crip aesthetic’ (Melkumova-Reynolds, forth coming), that subjective experience of disabled people are both complete and knowledgeable, and as an integral element in the discourse of fashion curation.